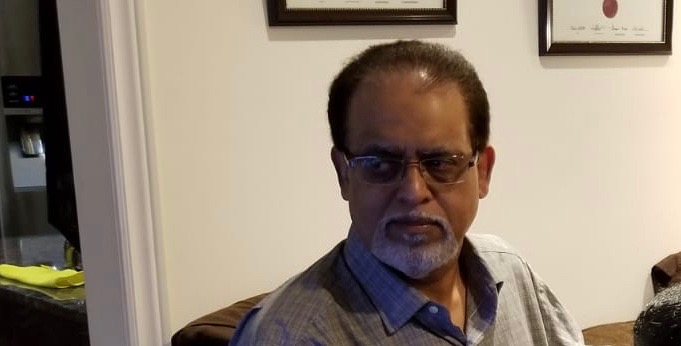

Life has been disorienting for Khalid Awan since he was deported to Canada from the United States, where he served a 14-year sentence for transferring money to a Sikh extremist group in Pakistan.

“It’s very hard,” he said.

Awan is among a handful of Canadians who’ve come home after having been imprisoned abroad for terrorism-related offences — in his case “providing money and financial services” to the Khalistan Commando Force.

Global News reported on Thursday that five terrorism offenders had been released from Canadian prisons in the past year, and three more could be let out in 2020.

But in addition to those exiting the Canadian corrections system, more with convictions for terrorism-related crimes have been returning to Canada from foreign prisons.

They include those imprisoned for their roles in Al Qaeda, the Tamil Tigers and Sikh extremism.

What happens when they return?

In Awan’s case, not much.

He lives in a basement apartment in Oshawa, Ont. His collection of replica swords decorates the walls. A mounted knock-off of John Wayne’s rifle hangs above the computer in his home office.

The 58-year-old former immigration consultant does not seem to concern Canada’s national security authorities. The only official visit he’s received came in the days after he obtained a new Canadian passport.

The officer who knocked on his door (his business card said he was from Public Safety Canada, but did not give his job title) left after 20 minutes, apparently satisfied because Awan was allowed to keep his 10-year passport.

Awan hasn’t tried to travel yet but doesn’t think he’s on any no-fly lists. He insists he’s not a threat to anyone, and was never really involved in terrorism anyway.

All he did was hang around the wrong people, he said.

“This is my biggest mistake.”

Asked what steps were taken when Canadians returned from abroad after serving terrorism-related sentences, the RCMP said offenders deemed threats could face management by government agencies, criminal investigations or terrorism peace bonds.

“The RCMP will assess and mitigate potential threats to public safety on a case by case basis,” said Cpl. Caroline Duval.

When he was deported back to Canada in the summer of 2018, Awan brought a long list of grievances with him. He calls his case a travesty of justice, and describes himself as a former political prisoner.

He’s trying to move on, but can’t let go. He’s filed three lawsuits in the U.S., and one in Canada. He made a complaint against the RCMP for assisting the FBI investigation. It was dismissed.

He wants an apology from Canada, which he alleges did not provide him with adequate consular services, or ensure he was treated properly in prison, where he says he was held in segregation, assaulted by a guard and denied Muslim-appropriate food.

“They never helped me,” he said.

He wants to sit down with Canadian political leaders and tell them the government failed him. His requests to meet them have so far been unsuccessful. He wants to write a book about what he went through.

He said he wants to open peoples’ eyes. He doesn’t want anyone else to go through what he did. He wants to send a message to the government: “Don’t play with the peoples’ lives.”

Despite his conviction, Awan denied being part of a fundraising network supplying a terrorist group. He said he thought the money he transferred to Pakistan was for wedding gifts and said his prosecution was punishment for refusing to work undercover for the FBI.

He said the leader of the Khalistan Commando Force, Paramjit Singh Panjwar, was his brother-in-law’s neighbour in Lahore and they would visit. He said Panjwar was supported by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency.

“He’s a VIP in Pakistan,” he said.

In his home office, Awan has catalogued his complaints in stacks of documents, some coded with coloured tabs. They tell the story of how he left Pakistan and, on May 25, 1992, arrived in Canada from New York hidden in the rear of a tractor-trailer.

He paid a smuggler to arrange the journey, he said.

His refugee claim was successful and he became a Canadian citizen in 1996, living initially in Montreal, then in Toronto, where he opened an immigration consulting firm before moving to New York to open a branch office.

He was living in Long Island when Al Qaeda struck the Twin Towers. He saw the buildings burn from his car, stuck in traffic, trying to get to a medical appointment in Manhattan.

Six weeks later, he was arrested as part of the 9/11 investigation. The FBI had received a tip that one of the hijackers, Marwan Al-Shehhi, was seen at Awan’s apartment before the attacks.

It was a mistake. The person seen at the apartment was not Al-Shehhi. But the FBI investigation turned up evidence of financial crimes, and Awan was charged with money-laundering and fraud.

Together with two others, Awan was alleged to have participated in a “bust out” scheme that used a shell company, Omega Techno Corp., to defraud credit card companies.

He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to five years. In interviews with Global News, he denied having committed any crimes.

On the eve of his release in 2006, he was brought back to New York. He thought he was being deported, but instead he was questioned about Sikh extremists.

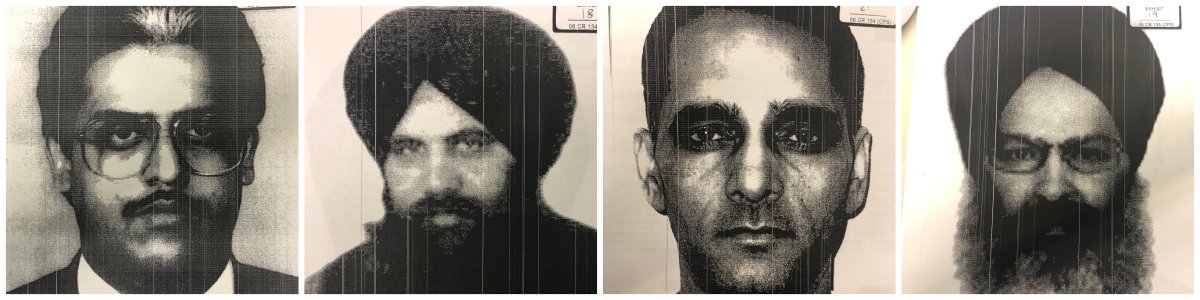

During searches of his belongings, federal agents had turned up a list of members and supporters of the Khalistan Commando Force, as well as a photo of its leader, Panjwar.

An inmate who had befriended Awan in prison, Harjit Singh, had also come forward, alleging the Canadian had told him about his close relationship with Panjwar and his role in funding the Commando Force.

The FBI wanted Awan to be a witness against two Sikh extremists living in the U.S. There was talk about sending him to India to collect information on Sikh extremist groups.

They also proposed training him to spy on Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program in his home village, the site of the Khusab Nuclear Complex, which produces weapons-grade plutonium, he said.

In Awan’s telling, it got dirty, with the FBI threating to turn him over to the Indian government unless he cooperated. He also claims the FBI would recommend him for a death sentence or arrest his wife in Pakistan and sisters in Montreal.

He refused to work for the FBI but made what U.S. prosecutors called “detailed admissions” about transferring money to Panjwar and his group, knowing the money was to be used for attacks against India.

Prosecutors charged him with three counts alleging he had been a “conduit” for Khalistan Commando Force supporters in the U.S., helping them transfer money to the Sikh terrorist group’s leadership.

Awan told Global News there was nothing to the case. The names the FBI found were potential clients, and the photo of Panjwar was taken at a wedding, he said. He admitted to phoning Panjwar from prison but said it was just to say hello.

He denied recruiting Singh into the KCF, and said the FBI misrepresented their conversations, which were only about visiting Pakistan to see Sikh holy sites and local theatre productions.

At the trial, prosecutors introduced recordings in which Awan “detailed how he had transferred funds raised in the United States for the KCF to Panjwar,” according to court documents.

Gurbax Singh and Baljinder Singh, alleged to be supporters of the Sikh extremist faction who had hosted fundraising gatherings at their homes, both testified they had used Awan to transfer $2,000 each to Panjwar.

The money was sent as wire transfers, sometimes to a cement pipe factory in Lahore, where Panjwar would pick it up. Awan would later phone to confirm Panjwar had received it, prosecutors alleged.

Meanwhile, Harjit Singh testified that Awan had talked about taking him to Pakistan following his release to meet Panjwar and undergo training on “how to use the guns, how to make the bombs.”

Following a three-week trial, a jury convicted Awan on all three counts. Prosecutors wanted a 45-year sentence but Awan’s lawyer argued he had never provided any arms to the KCF, nor committed any violence.

The judge found that Awan was not really motivated by terrorism, or a desire to fight India. Instead, he had a need to drop names and associate with powerful people. He was sentenced to 14 years.

For years of his imprisonment, Awan was segregated and held in a communications management unit, where inmates convicted of terrorism offences were kept under restrictive conditions.

He was initially limited to a single three-minute phone call per month, he said. The prison flooded, and the windows wouldn’t close, letting in drafts, and there were rats and mice, he said.

He wrote letters to Canadian MPs and went on a hunger strike.

When it was over, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement brought him to the Fort Erie border crossing and handed him to a Canada Border Services Agency officer, who gave him coffee and gum.

He said he wept upon getting back on Canadian soil. Even recalling the moment, he teared up. “It’s very hard to explain,” he said. He boarded a bus and made his way home to his family.

It was an adjustment.

After years of prison food, he could no longer stomach South Asian dishes. He had trouble sleeping. He was prone to silences. His wife wouldn’t let him talk about prison in front of the grandchildren.

Hoping to resume his immigration consulting career, he enrolled at college, so he could catch up on all he’d missed, although he’s unsure he will be allowed to practise because of his criminal record.

“Life is not easy,” he said.

Source: Global News