After lingering in the backdrop of the discussion through much of the presidential race, climate change has been thrust to the forefront as the Trump campaign rushes to build a closing argument around Joe Biden’s plan to fight global warming.

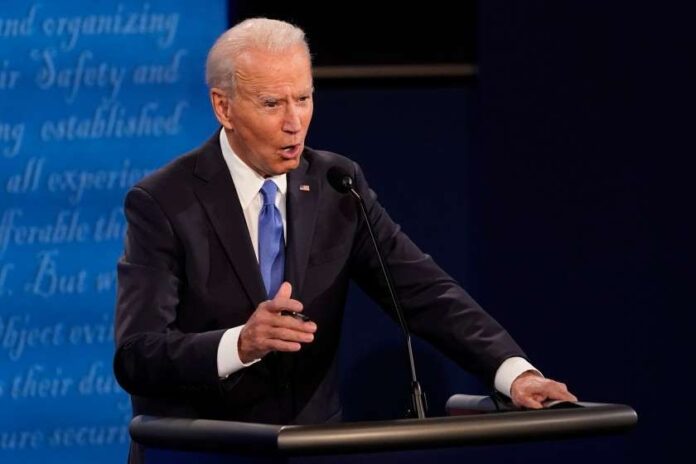

Biden’s comment at Thursday night’s presidential debate that his climate action plan would eventually doom the oil industry unleashed a coordinated attack by the GOP in swing states. But the strategy of going after Biden on fossil fuels may be coming too late — by about a decade, experts on the subject said.

Voters are far more bullish on phasing out fossil fuels than they have ever been, polls indicate.

Still, Biden’s remarks did create headaches for his party, especially in congressional districts with a large oil-industry presence. The post-debate flare-up reflected the thorny politics of pushing a major energy transition — even one popular with a large number of voters — at a time when so many Americans are out of work.

Within minutes of the end of the debate Thursday night, Democratic House incumbents in New Mexico and Oklahoma had distanced themselves from Biden’s comments, saying they would not be part of any effort to villainize a crucial industry in their states. And Biden quickly backpedaled from some of what he said on the stage.

By Friday, senior Republicans were declaring — perhaps a bit wishfully — that voters in swing states where Biden has led for months would abandon him.

“This probably will put the nail in the coffin for Joe Biden in Pennsylvania,” Jason Miller, a senior advisor to Trump’s campaign, said on a call with reporters Friday. He said the remark would also cost Biden votes in Michigan and Ohio. “This is really devastating.”

The remark at issue came in the debate’s closing minutes.

“I would transition from the oil industry,” Biden said. “It has to be replaced by renewable energy over time — over time,” he added after Trump interrupted him. “And I’d stop giving to the oil industry — I’d stop giving them federal subsidies.”

Trump pounced on the comment Friday afternoon at his first rally after the debate, at the central Florida retirement community the Villages.

“One of the most stunning moments last night was when Joe Biden admitted that he wants to abolish the oil industry,” Trump told a cheering and packed crowd. “Did you see him this morning? This morning: ‘I didn’t really mean that,’” Trump said, mocking Biden.

“That could be one of the worst mistakes made in presidential debate history,” he said. “We hope it is.”

Biden’s running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris, campaigning Friday in Georgia, sought to defuse the issue by stressing Biden’s position on the energy issue that has generated the most attention among Pennsylvania voters.

“Let’s be really clear about this,” she said. “Joe Biden is not going to ban fracking. He is going to deal with the oil subsidies. But that’s — you know, the president likes to put everything out of context. But let’s be clear: What Joe was talking about was banning subsidies, but he will not ban fracking.” Harris herself supported a fracking ban during the Democratic primaries.

Despite the Republican eagerness, Democrats were not showing signs of panic in Pennsylvania, a closely fought state crucial for both sides, where Biden’s positions on oil and natural gas have been the subject of intense debate for months.

“Biden said something out of order, maybe even clumsy,” said Rich Fitzgerald, the executive for Allegheny County. “But everyone here already knows what his policy is, and it hasn’t changed.”

Fitzgerald is among the Democratic officials in southwestern Pennsylvania who have lobbied Biden to stress support for fracking of natural gas and to avoid bashing fossil fuels.

Pennsylvania Lt. Gov. John Fetterman, a Biden supporter who has cautioned Democrats against unrealistic timetables for phasing out oil and gas, predicted Trump would win few new voters with his latest attack.

“Maybe a couple of months ago this would have shaken things up,” he said. “But if you are in the small group voting on this issue, you already know exactly where both candidates stand.”

Biden’s climate blueprint has been around for months, and his debate-night comment didn’t break new ground on policy, although its unartful wording created a new opening for Trump to cast him as a radical.

Biden left the impression that his proposal could shut down oil production by 2035, which it would not do. The target in his plan for phasing out all fossil fuel use is not until 2050. Biden also conflated his push to quickly end subsidies for oil and gas with that decades-long phaseout of the fuels.

Shortly after the debate, the candidate sought to do some cleanup.

“We’re not getting rid of fossil fuels,” Biden told a gaggle of reporters Thursday night at the airport in Nashville before boarding his plane for home. “We’re getting rid of the subsidies for fossil fuels, but we’re not getting rid of fossil fuels for a long time.”

But it was too late to contain all the fallout. Oklahoma Rep. Kendra Horn, a Democrat and one of her party’s most endangered freshmen, already had written on Twitter that she disagreed with Biden’s comments and that “we must stand up for our oil and gas industry.”

Another House Democrat in an oil state, Xochitl Torres Small of New Mexico, also expressed disappointment over Biden’s exchange with Trump. “We need to work together to promote responsible energy production and stop climate change, not demonize a single industry,” she tweeted.

Nationally, however, scholars who have been tracking public opinion on fossil fuels said Trump’s latest foray struck them as futile.

“Many people within Washington, D.C., including the Trump campaign, think this is somehow going to help them, and it isn’t,” said Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale University Program on Climate Change Communication. He said 71% of Americans support the type of phaseout of fossil fuels contained in the Biden plan, according to polls sponsored by his group.

Support for phasing out oil and gas is popular even in places where the fossil fuel industries are strong, Leiserowitz noted. The GOP push to make climate action a political liability, he said, reflects the public’s mood in the 1990s and early 2000s, when renewable energy was considerably more costly and far less integrated into the economy.

“I don’t see it helping them anywhere,” he said.

Source: Los Angeles Times